House Ways and Means Committee Testimony—January 25, 2024

Hi everyone, thanks for having me back. Again, I’m Stephanie Yu, Executive Director of Public Assets Institute. I just want to make a couple of quick points about what all this great work (and clear, thoughtful methodology behind it) from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) means.

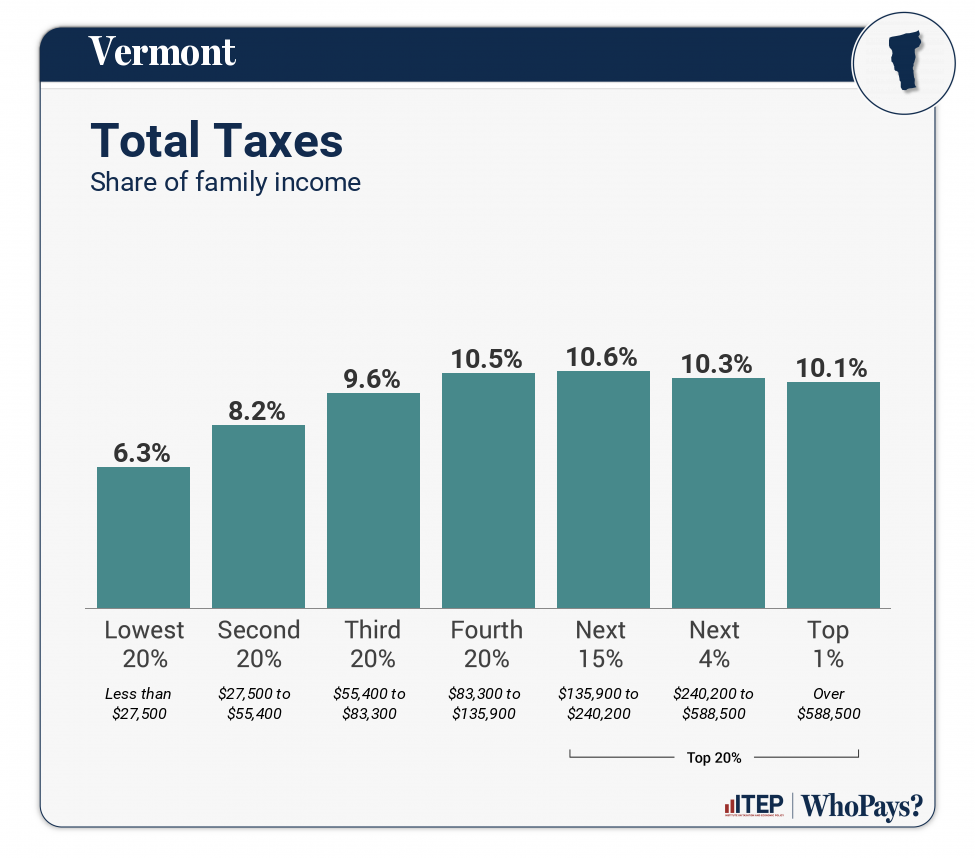

First, that the goal is a progressive tax system; we’ve heard now that our tax system actually improves income inequality unlike so many states, but that it remains regressive at the top end and is not truly a progressive system.

First, that the goal is a progressive tax system; we’ve heard now that our tax system actually improves income inequality unlike so many states, but that it remains regressive at the top end and is not truly a progressive system.

So what’s the best way to make our system more progressive? Do we need to increase taxes on the high end or decrease them on the low end? I think the answer is both.

I would say the first step is eliminating the regressivity at the high end. Vermonters making $90,000 or $140,000 a year should not be paying a greater share of their income in taxes than those making $500,000 or $1,000,000.

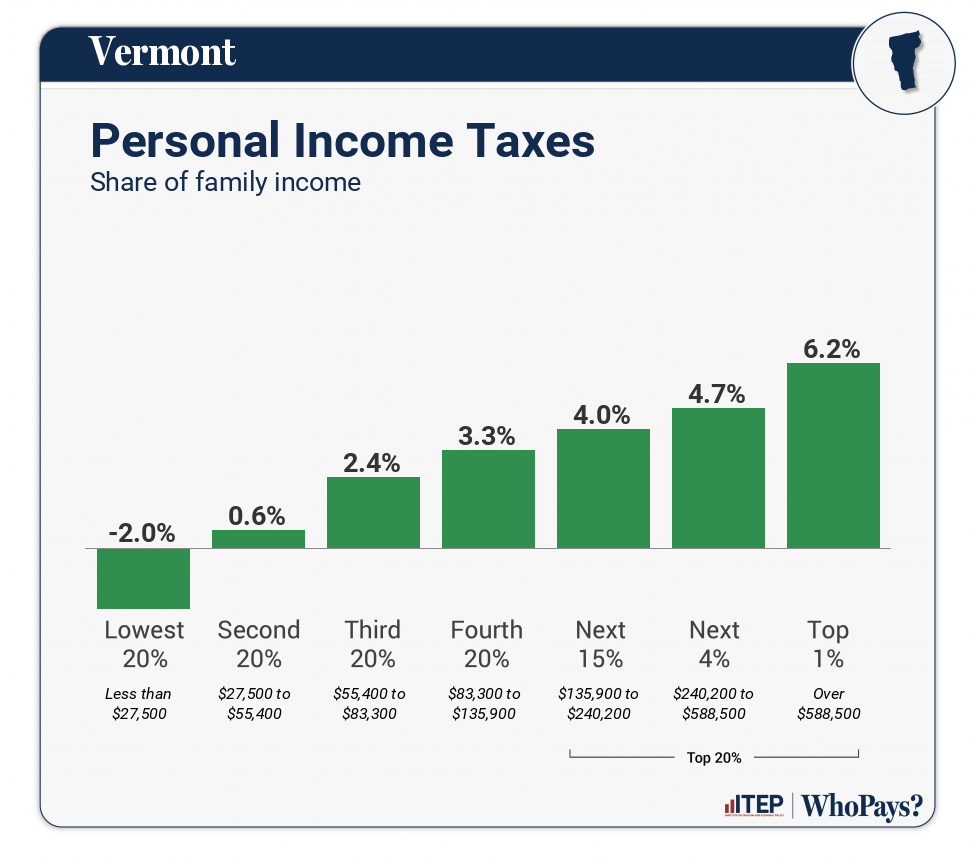

ITEP’s work makes it clear that is currently the case. So we want to start by making sure the overall system looks more like the income tax chart and actually is a clean line going up, rather than the bumpy, uneven version we’ve had. And the best way to do that is to focus on taxing those high-income Vermonters. In fact, that’s the best way to ensure we can maintain a progressive system for everyone—that those at the top are contributing according to their ability to pay. Otherwise, it’s fair to say that those paying more—the middle class—are subsidizing the highest-income Vermonters.

ITEP’s work makes it clear that is currently the case. So we want to start by making sure the overall system looks more like the income tax chart and actually is a clean line going up, rather than the bumpy, uneven version we’ve had. And the best way to do that is to focus on taxing those high-income Vermonters. In fact, that’s the best way to ensure we can maintain a progressive system for everyone—that those at the top are contributing according to their ability to pay. Otherwise, it’s fair to say that those paying more—the middle class—are subsidizing the highest-income Vermonters.

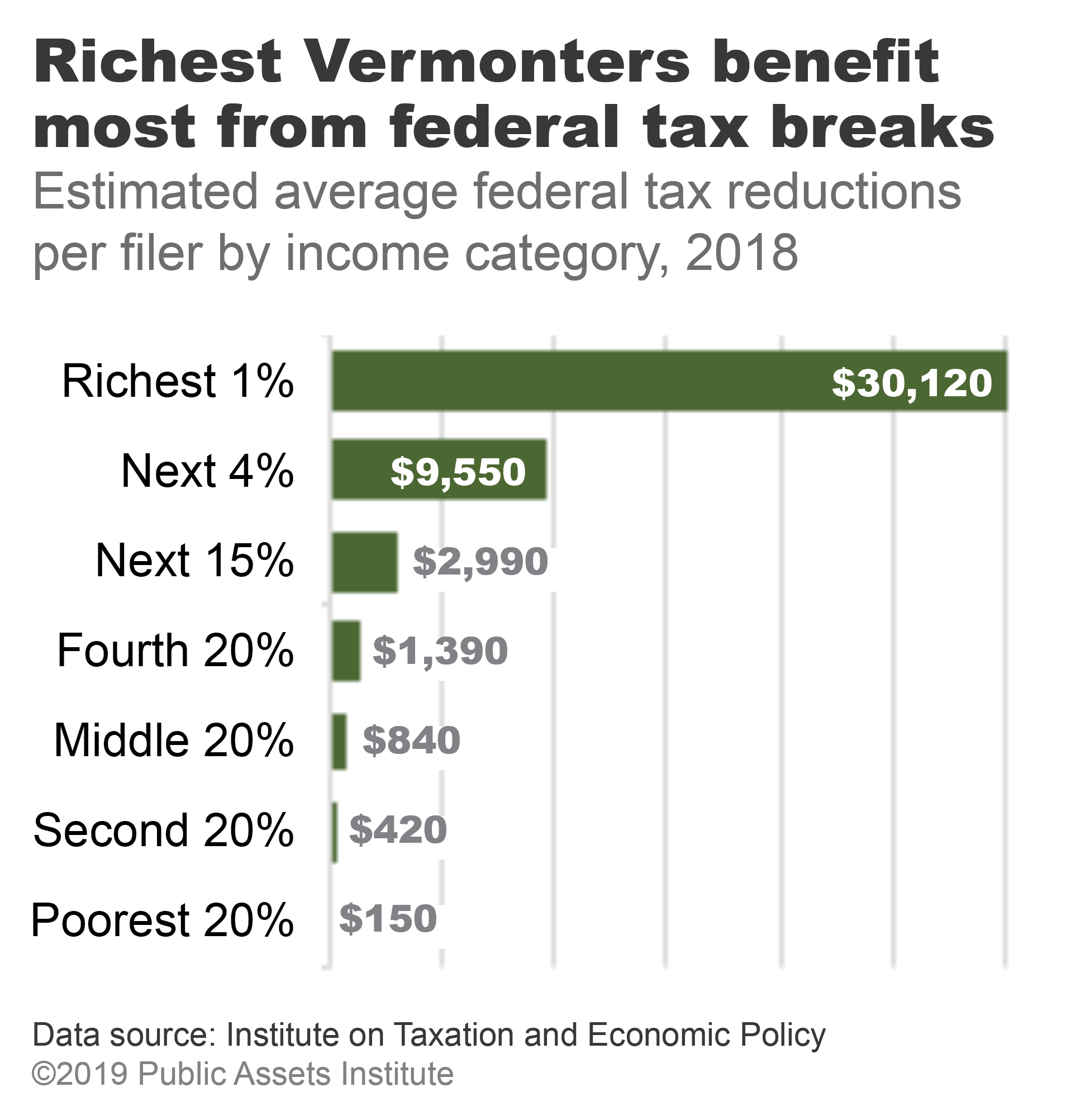

Another thing worth noting here is that while we’ve been focused on the state tax system in this conversation, at the federal level, the personal income tax has gotten less progressive. I mentioned last week that our income tax is really based on the federal model. The federal income tax is still a progressive tax, but the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2018 disproportionately benefited higher-income taxpayers. Again, more great work from ITEP here showed that if the provisions in TCJA are extended, the top 1% of Vermonters will see over $80 million in tax cuts in 2026 at the federal level, an average break of over $24,000 per filer. And they’ve already been experiencing those benefits since 2018 and will through 2025 (these are the 2018 numbers because I didn’t have time to make a new chart, but the shape is the same). And we know that over the last 40+ years, tax cuts at the federal level have largely accrued to the rich. So I think it’s fair to say that there is plenty of taxing capacity in Vermont.

Another thing worth noting here is that while we’ve been focused on the state tax system in this conversation, at the federal level, the personal income tax has gotten less progressive. I mentioned last week that our income tax is really based on the federal model. The federal income tax is still a progressive tax, but the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2018 disproportionately benefited higher-income taxpayers. Again, more great work from ITEP here showed that if the provisions in TCJA are extended, the top 1% of Vermonters will see over $80 million in tax cuts in 2026 at the federal level, an average break of over $24,000 per filer. And they’ve already been experiencing those benefits since 2018 and will through 2025 (these are the 2018 numbers because I didn’t have time to make a new chart, but the shape is the same). And we know that over the last 40+ years, tax cuts at the federal level have largely accrued to the rich. So I think it’s fair to say that there is plenty of taxing capacity in Vermont.

But I also want to spend a minute focused on the lower-income end of the scale. Vermont should be proud that not only are we one of the least regressive states, we’ve gotten even more progressive at the low end—again, that’s largely due to increases in the EITC and the dependent care credit, as well as the implementation of the state Child Tax Credit. We use these refundable credits to return money through the income tax system to lower-income Vermonters—which is why the lowest 20% show up as negative in that chart.

But it’s not enough.

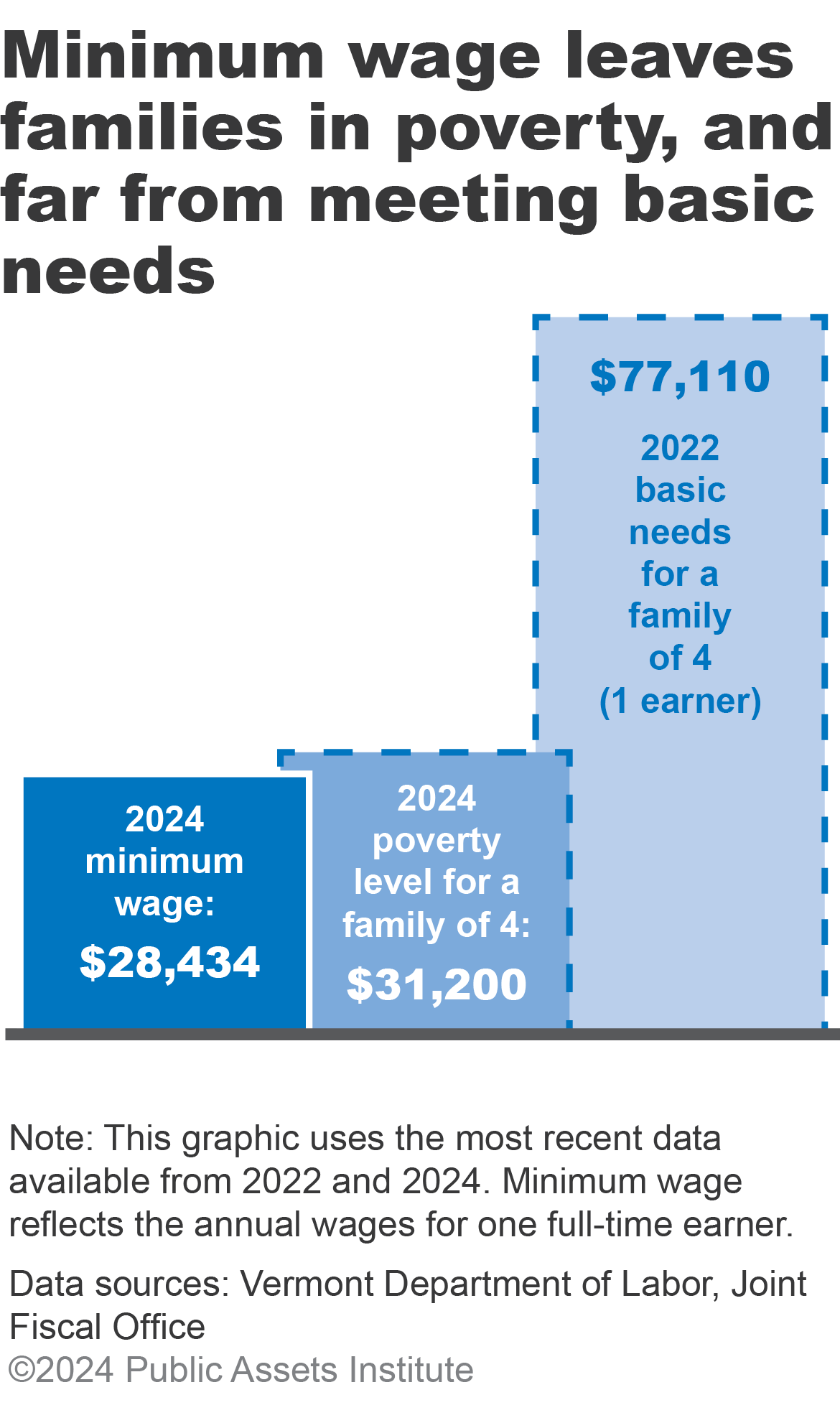

Vermont produces the Basic Needs Budget every two years. I know there’s been work on how and whether to tweak the methodology of that report, but I think at its core it’s one helpful tool that not many states have, and that we should be using it to have a better sense of how families are doing and to help measure how far we have to go to make sure all Vermonters can thrive. Often tax credits and benefit programs are looking at the poverty level as a way of establishing eligibility, but I think Vermont as a state has recognized that that threshold is way too low and really understates which families are struggling to make ends meet.

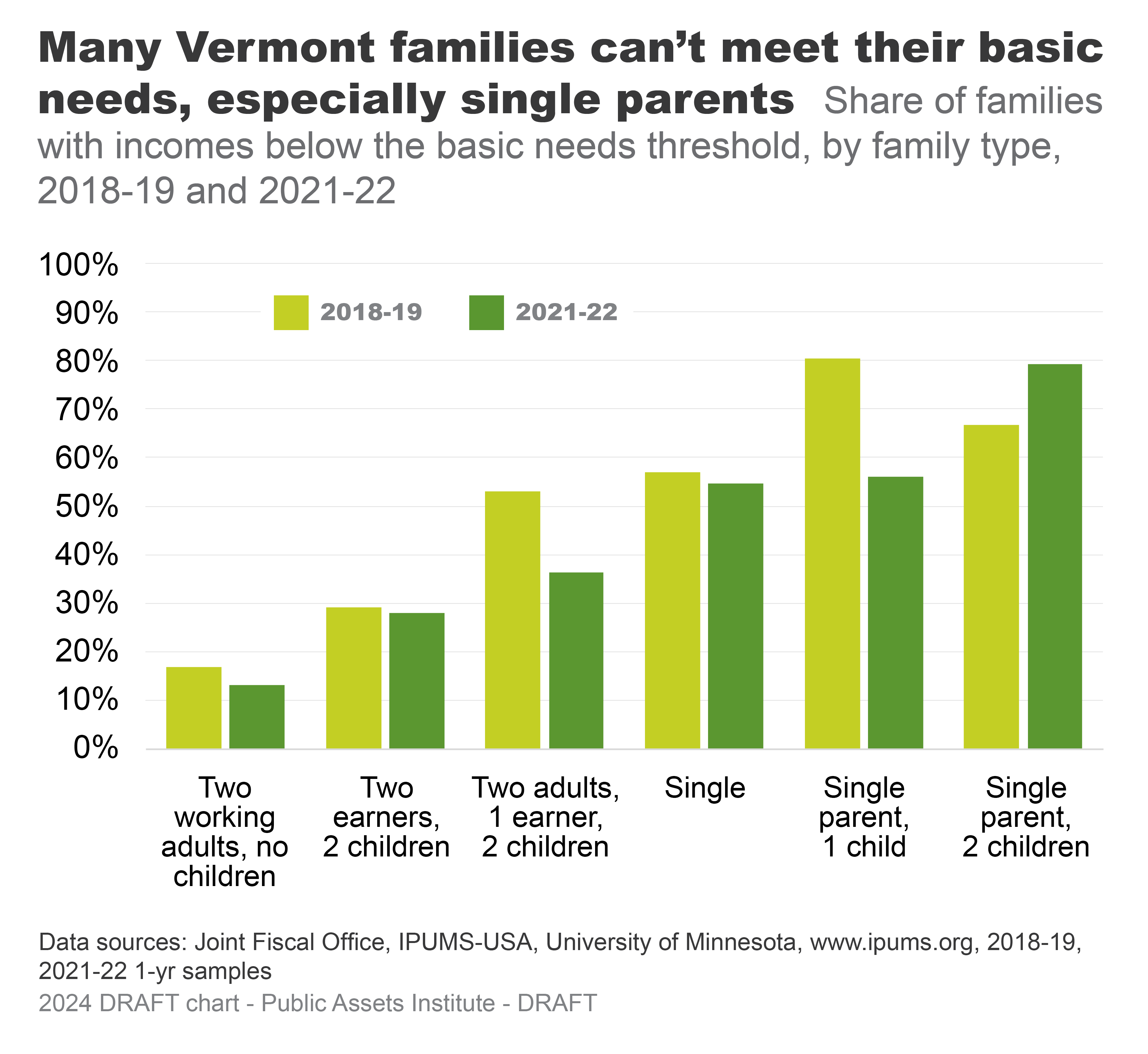

And that’s where the Basic Needs Budget comes in. Again, I think we can tweak the methodology, but those tweaks are not going to change the underlying reality: there is a huge gap between what we call poverty and what it really takes to support a family of any size. Just to put that in perspective, here’s the difference for a family of four. And this includes the minimum wage so you get a sense of what that poverty level means. We also do an analysis on the Basic Needs Budget to look at which family types have enough income to meet their needs and this is the latest. This is a preliminary chart for a report we’re working on. It doesn’t look at every family type but at some of the most common ones. The good news is that there was improvement across most family types between 2018-19 and 2021-22. That’s likely because of the temporary expansion of federal credits during the pandemic, as well the stimulus payments, increased unemployment benefits and all the other Covid programs that helped individuals and families. But the bad news is that even with that additional aid, many families could not meet their basic needs. The majority of single parents struggled, which might not be that surprising. But it’s striking that even with two earners, a third of families with two children struggled. And it’s also worth noting that more than half of single people fell short of what they needed.

And that’s where the Basic Needs Budget comes in. Again, I think we can tweak the methodology, but those tweaks are not going to change the underlying reality: there is a huge gap between what we call poverty and what it really takes to support a family of any size. Just to put that in perspective, here’s the difference for a family of four. And this includes the minimum wage so you get a sense of what that poverty level means. We also do an analysis on the Basic Needs Budget to look at which family types have enough income to meet their needs and this is the latest. This is a preliminary chart for a report we’re working on. It doesn’t look at every family type but at some of the most common ones. The good news is that there was improvement across most family types between 2018-19 and 2021-22. That’s likely because of the temporary expansion of federal credits during the pandemic, as well the stimulus payments, increased unemployment benefits and all the other Covid programs that helped individuals and families. But the bad news is that even with that additional aid, many families could not meet their basic needs. The majority of single parents struggled, which might not be that surprising. But it’s striking that even with two earners, a third of families with two children struggled. And it’s also worth noting that more than half of single people fell short of what they needed.

So I think there’s a strong case for both raising the rates on the high end and increasing the credits on the low end. We want the system to be progressive, which means we need to get rid of the regressivity at the top and ensure that middle class Vermonters aren’t paying more than those with the highest incomes. We also want Vermonters to be able to meet their basic needs, and many are falling short no matter how we define that, so we need to improve the bottom end too.

Ms. Yu, you might want to check w/ Ms. Heilweil of Fund Vermont’s Future about a “max cap tax” system for a really equitable, progressive and simple system that would cut taxes from at least 17% to 100% for everybody earning less than a million dollars.

Did I submit this suggestiion once before? Can’t recall. Anyway, can income be effectively spread out more by raising the circuit breaker? It was $47,000 years ago. Don’t know what it is now. What if it went to say $65,000. And Income Sensitivity was equally adjusted. Presumably that forces higher tax rates at the upper end to produce the same tax revenue.

That’s a great point, Spoon. Ensuring the circuit breaker keeps up with inflation makes good policy sense and would help lower-income Vermonters with both school and municipal taxes. But unlike most states where property taxes are wholly regressive, Vermont’s system of basing school taxes on income means that our property tax is progressive for most taxpayers. The problem is on the high end: richer Vermonters pay based on property value, which is a better deal for them and makes the system regressive at the top. Income-based school taxes for all Vermonters would eliminate that regressivity and move our whole revenue system in a more progressive direction. – Steph

Thanks for your comment cgregory. Fund Vermont’s Future is currently advocating for a surcharge on high incomes and a tax on unrealized gains for the wealthiest Vermonters, but the coalition continues to explore other policy options to ensure that Vermont’s tax system is progressive and raises sufficient revenue to adequately address the needs of all Vermonters. We welcome your feedback and policy proposals as our advocacy evolves. – Anika