There’s more to school tax increases than spending

Problems old and new undermine fairness for some taxpayers and districts

Vermonters have been understandably upset by the abrupt rise in their school taxes for fiscal 2025. Most of the complaints focus on the rise in spending, as does the response from policymakers. But taxpayers may also be affected by changes that make the funding system less fair.

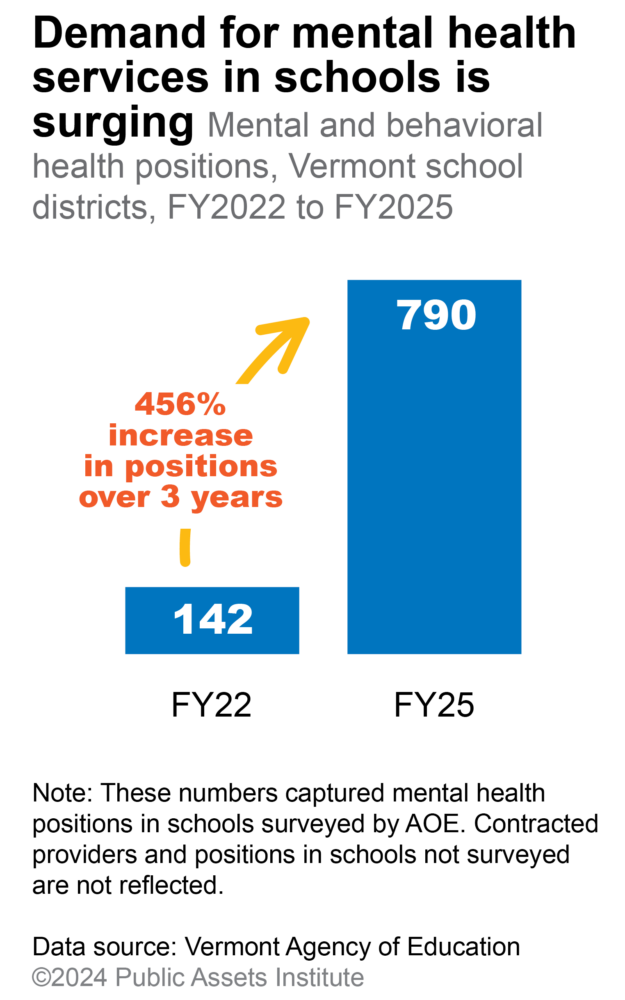

The Agency of Education presented some clear analyses last spring explaining the main reasons for the spending increase: rises in salaries and benefits in response to inflation; health insurance cost increases exceeding inflation; the expanding need for expensive mental health services for students; the loss of federal funds the schools received as part of the pandemic-related American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). There are other reasons as well, related to fiscal decisions made in the past few years. The expenditures are critical for providing kids with a quality education. But knowing that doesn’t make the tax bumps easier to take. Even modest increases can be a problem if the costs, and who pays them, are not distributed fairly.

Homestead taxes increased by 12.9% in FY2025

In fact, some districts and taxpayers have been facing disproportionately higher bills for a while. For fiscal 2025, Vermont is using a new system of student weighting that is supposed to make it easier for communities to raise and spend money for students that need additional resources, including students in poverty and students attending small, rural schools. The changes are intended to level the playing field for these kids. But there are other costs that also affect school districts differently. For example: In 2018 Vermont changed the way it distributes funding for special education. The disbursement is no longer based on the number of children to whom a district provides special education; it’s calculated by the district’s share of the state’s total school population. That shifts additional costs onto school districts where special ed students make up larger proportions of the student body.

Another factor: Mental health providers and services are unevenly available around the state. That means some schools have to hire their own specialists at higher costs than districts that can contract with local providers. And the demand for mental health positions has more than quadrupled in the last three years, compounding the impact.

School mergers may also be contributing to a sense of unfairness in the system, as larger communities in consolidated districts push to close smaller schools to save money. But no good analysis has been done about whether closing schools meaningfully cuts costs—or how school closures might affect students or communities.

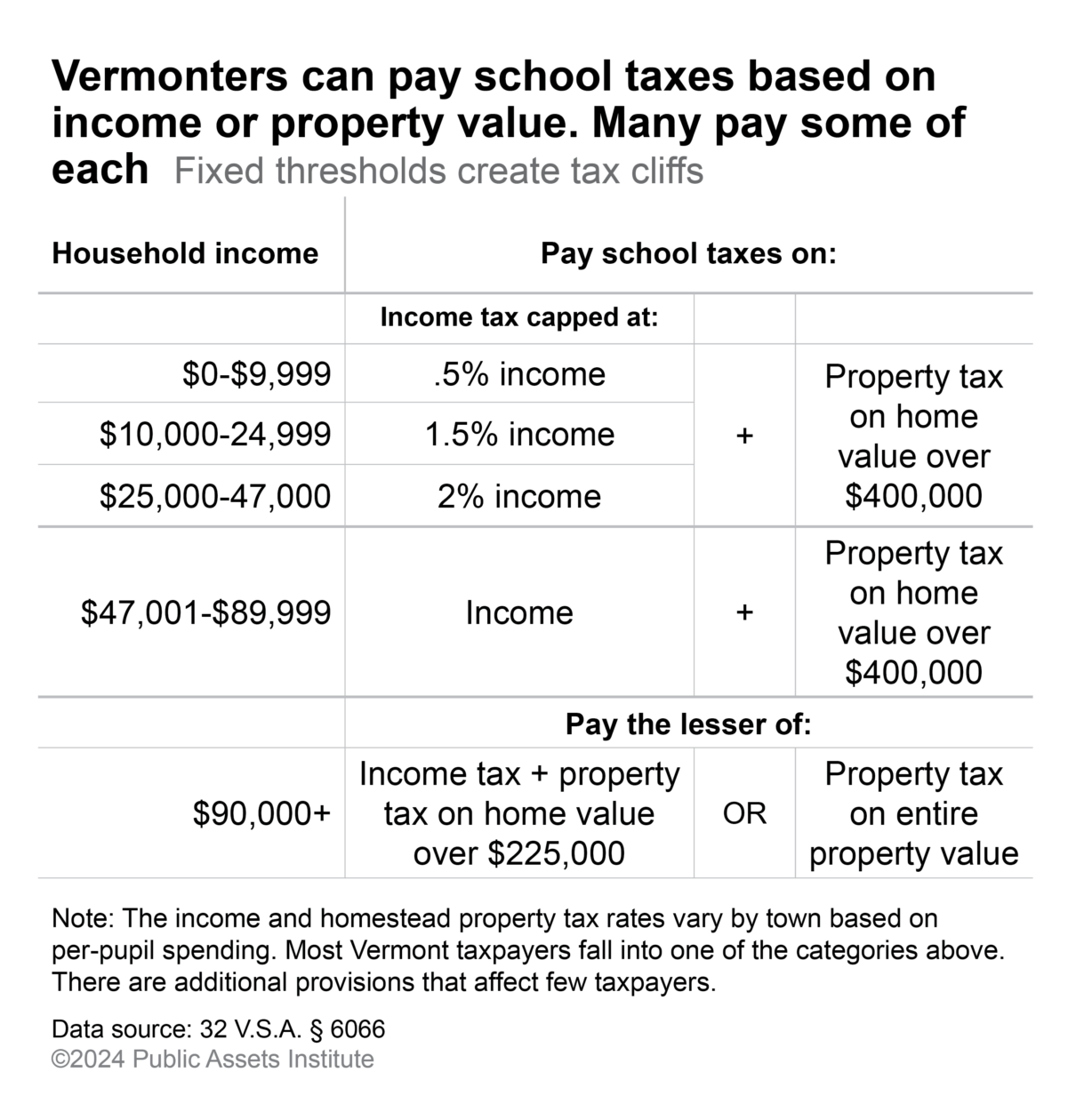

There are also inequities in who pays school taxes. Vermont’s funding system gives resident homeowners the option to pay school taxes based on their income or the value of their homes. Built into the system are thresholds on income and home values that require some low- and moderate-income people to pay both a school income tax and property taxes on a portion of their home’s value.

The thresholds create tax “cliffs,” where an extra dollar of income or a property reappraisal can have disproportional tax consequences. The thresholds have not been raised or adjusted for inflation in years. And because incomes and property values have grown, more and more Vermonters are hitting these cliffs. Homeowners who cross the $47,000 income threshold can see a school tax increase of 10, 15, 25 percent or more. A family with a $350,000 home that crosses the $90,000 income threshold could see a 70 percent jump in school taxes.

A lot of factors, many beyond Vermont’s control, came together to create a spike in school spending and taxes for fiscal 2025. And some districts and their taxpayers were hit harder than others. But because of the cliffs, taxpayers can see spikes in their bills even when spending doesn’t jump.

This means that spending cuts won’t address either of these challenges—disparate costs from district to district or the inequities low- and moderate-income taxpayers face.

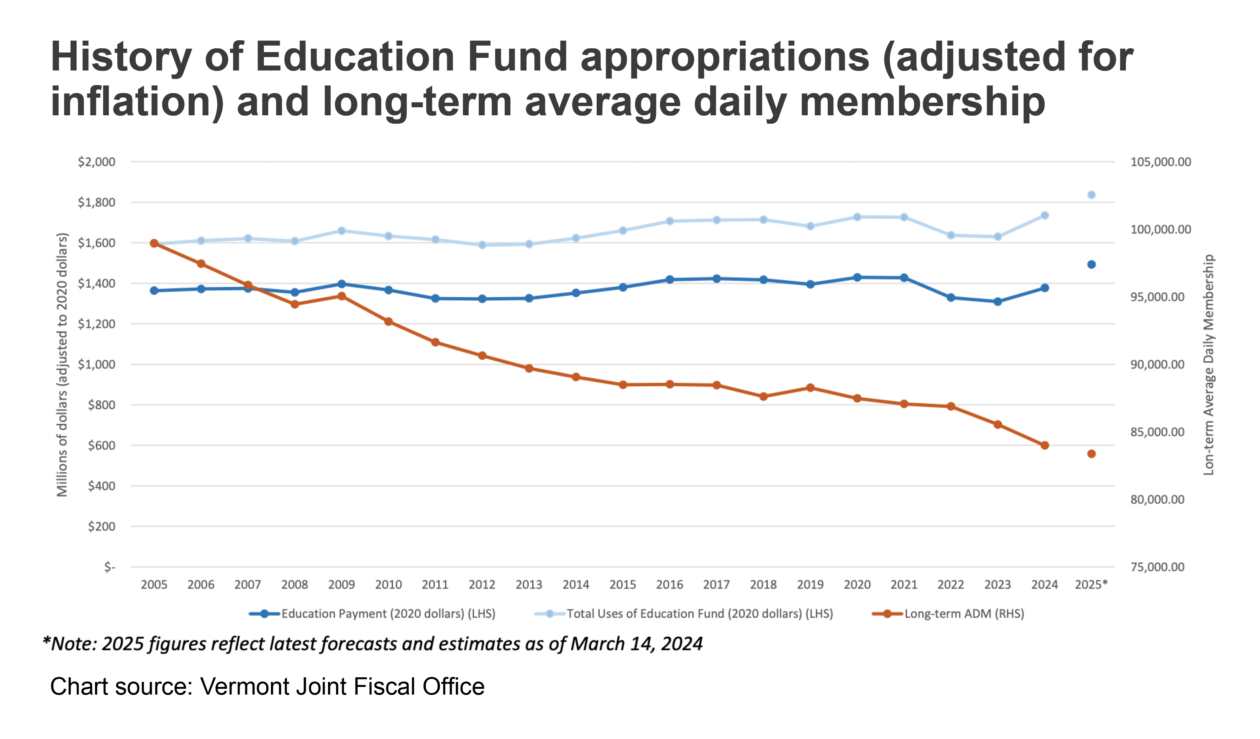

In fact, local voters have done a good job of controlling education costs over the last two decades. Adjusted for inflation, education spending was flat from fiscal 2005 to fiscal 2024, according to the Legislature’s joint fiscal office. And while the number of students (long-term average daily membership) has declined over that period, again after adjusting for inflation, the average annual increase in per-pupil spending was less than 1 percent per year.

The main goal of our education funding system is clear: the best education we can provide for every child. Voters have to decide each year how much to spend in their districts, but their ability to make good decisions can be undermined if costs fall unfairly on districts and taxpayers. Cost containment won’t address unfairness, reduce the need for mental health services, or bring down insurance premiums for educators. But eliminating these inequities would make the system fairer and keep the focus where it belongs: on Vermont kids.

I was part of the Safe Community Schools group that helped Lincoln separate itself from MAUSD. I’ve been asking legislators for a while to study the impact of act 46 to see if it really made education better and contained cost. I’ve gotten nowhere with this. Actually, I think small schools do better at controlling cost and providing quality education. Lincoln is a good example of that. Plus small schools in a community add to the vibrancy of the community.

It defies logic to constantly see declining student population while experiencing significant education spending.