Vermont response to federal actions:

What is already happening and what else is needed?

See more

See more

There have been a lot of changes to federal policy in recent months that are affecting Vermonters. Some have taken effect, some have been proposed and are under consideration, some have been implemented and then reversed, and some are working their way through court challenges. We will keep this page updated as much as possible as new changes happen.

If these were ordinary times, we would expect Gov. Phil Scott to deliver his usual budget address calling for more of the same spending and revenue policies. But these are not ordinary times. The relationship between Washington and the states has fundamentally changed. The states are facing unprecedented federal cuts, spending freezes and abrupt changes to essential services. This new reality requires a new approach to revenue. Vermont, along with the other states, are going to need to reclaim the money used to provide federal tax cuts to the wealthy. Less help from the federal government doesn’t make us helpless. We can take matters into our own hands and ensure Vermonters get the services they deserve.

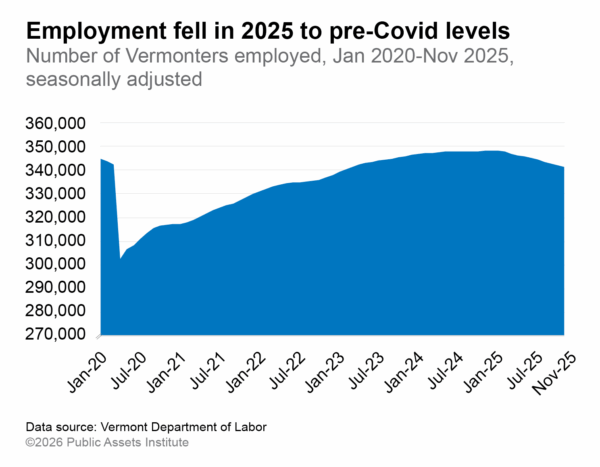

After years of steady growth, the number of Vermonters working fell below pre-pandemic levels in late 2025.

It took more than three years for Vermont employment to return to normal in the wake of Covid. By early 2024, the number of Vermonters working exceeded the number employed before the crisis. Monthly employment reached an all-time high in January 2025, at 348,340. Then it dropped every month through November.

In many ways, 2025 has been a year like no other. Federal actions affecting the state have been fast and furious: freezing grants, eliminating housing supports, withholding or slashing food benefits and heating assistance, decimating healthcare access both by cutting Medicaid and ending enhanced insurance premium tax credits. All of this adds up to hundreds of millions of dollars in lost federal support, both to many individual Vermonters and to the state. The primary objective: to finance tax cuts for corporations and the rich.

These are not the only federal policies that have immediate, measurable consequences for the state. Causing unprecedented harm to the security and prosperity of Vermonters are the near elimination of global public health resources, the loss of critical data collection, layoffs of federal workers by the thousands, and a campaign of lawless, aggressive, and indiscriminate immigration enforcement.

At the same time, the story this report tells about Vermont is familiar.

Recent major changes and minor tweaks to Vermont’s education funding system have added complication and confusion. They’ve made it harder for Vermonters to understand the connection between school budgets and tax bills or see how spending and tax rates have changed over time. With metrics and calculation methods changed, it is more difficult to compare education funding data from fiscal 2024 and earlier with data since fiscal 2024 to assess whether the reforms are achieving their goals.

This edition of the town2town report offers readers a tool to view and assess their local education spending and tax data. In the interactive charts, readers can view tax rates and per-pupil spending from fiscal 2016 to fiscal 2026 in relation to the statewide averages. So, while the drop in per-pupil spending from fiscal 2024 to fiscal 2025 will be hard to interpret, readers can see whether their town moved closer to or farther from the state average in those years.

One of the main issues at stake in the federal government shutdown is the expiration of enhanced healthcare premium tax credits, which help people buy insurance through the state marketplace. If Congress does nothing, the credits will expire at the end of 2025, and millions of Americans will see large increases in the cost of their healthcare.

Over 30,000 Vermonters get health coverage through the state exchange. And because Vermont has the highest premiums in the country, Vermonters no longer qualifying for the credits will see the biggest increases. Middle-income participants are looking at an additional $10,000 a year for an individual and $32,000 for a family of four.

How the credits work

Vermont’s health insurance marketplace launched in 2014 as part of the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA). The goal was to provide access to affordable health insurance to consumers who can’t get it through work or public programs. The ACA requires every state to operate an exchange with multiple qualified health plans and helps cover the cost of the premiums.

The Act 73 Redistricting Task Force wrapped up their work today, and they’ve given the state a chance to rethink the course of education reform it has been pursuing for the last decade. Vermont communities, as well as elected leaders, should seize this opportunity to get us out of the ditch we’ve been in and refocus on what should be our priority: ensuring our kids have what they need to thrive.

The 168-page draft proposal from the November 10th meeting of the Task Force had a lot to digest. And it requires close reading because the proposal offers much more nuanced analyses of problems confronting the education system than we’ve seen from the administration or the Legislature in recent years. The Task Force also put out a more streamlined draft report today along with an explanation of the changes.

One of the group’s most important recommendations is to stop further forced consolidation of school districts, which fits with one of the Task Force’s guiding principles: Do no harm. It’s not that the committee opposes mergers. It recommends voluntary consolidation for some districts in certain circumstances, which was the state’s policy before passage of Act 46 a decade ago.

Now that the government shutdown is over, maybe the federal game of chicken over SNAP benefits will end too. That fight showed just how critical state action is to protect the safety and security of Vermonters.

Thanks to the foresight of Vermont legislators this spring coupled with their quick action last month, thousands of Vermonters were able to access food assistance despite the federal government’s refusal to pay.

Facts still matter, and the proof of that is becoming more and more evident as we continue to lose access to valuable federal government data.

Today is the day we would normally be getting information about the number of jobs employers added or cut last month. We would have learned if the number of Vermonters who are out of work rose or fell. And we should have gotten data on the ratio of job openings to the number of people looking for work, which could shed light on Vermonters’ employment prospects heading into the fall.

Thousands of Vermont’s federal workers are at risk of getting furloughed or fired under the government shutdown which began on October 1st. Even with a continuing resolution in place, hundreds of millions of dollars in grant funding to Vermont could be at risk and lead to programmatic funding cuts, particularly in high-inflation sectors.

Congressional leaders failed to reach an agreement on a funding bill. As a result, federal discretionary funding expired on September 30th, 2025 at midnight, the end of the 2025 federal fiscal year (FFY). While discretionary funding accounts for only about a quarter of all government spending, nearly half of this amount is allocated toward employee benefits and pay, making it a significant funding source for federal workers. Until Congress takes action, many federal programs won’t be able to operate, many essential federal employees will be working without pay, and federal employees considered non-essential will not be able to work. Employees typically receive back pay when the shutdown ends, but the administration has suggested some furloughs will become permanent this time.

Recently, residents of the town of Windham wrote about how their neighbors on fixed incomes saw a nearly four-fold increase in their property tax bills after a town-wide reappraisal this year.

Concerned that big hikes would force folks out of their homes, the authors wondered why these low-income Vermonters, who according to Vermont statute should pay no more than 4.5 percent of the income for property taxes, were now facing bills as high as 16 percent of their incomes?

It’s a good question.

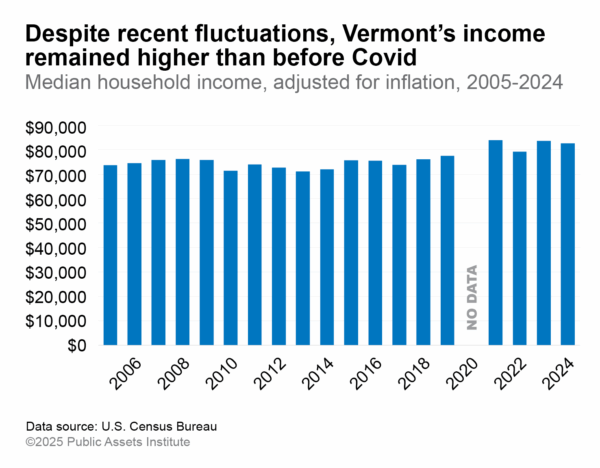

Newly released U.S. Census data show that Vermont’s median annual income decreased last year to $82,730 after adjusting for inflation. While this change was not statistically significant, Vermont was one of only six states nationwide where income declined. Only North Dakota and Rhode Island saw sharper drops. This marks a departure from the income growth Vermont experienced immediately after the start of the Covid pandemic: a rise of over 8 percent between 2019 and 2021, the fastest growth in the country.

After considerable confusion and dissent, the Legislature ultimately approved and the governor signed the education reform bill (Act 73) into law in July 2025 with the explicit goal of spending less on public education.

But neither the House plan nor the Governor’s plan address the two biggest problems we face in education funding:

• unfairness in who pays school taxes

• the biggest cost drivers out of districts’ control like teacher healthcare and inflation

And both plans are proposing some big structural changes that raise serious concerns:

• reverting to a foundation plan

• dismantling democratic participation in schools

• state-imposed school and district consolidation

• eliminating income-based taxes and doubling down on property-based taxes

Vermonters did not ask for another overhaul of our public education finance and governance system; they asked for tax relief. Our schools and communities are still reeling from the pandemic and the last decade of major changes imposed by the governor and legislature: consolidation, special education reform, and pupil weighting changes. The state has not provided any evaluation of the outcomes of those reforms, but there has been a lot of confusion and chaos and negative unintended consequences.

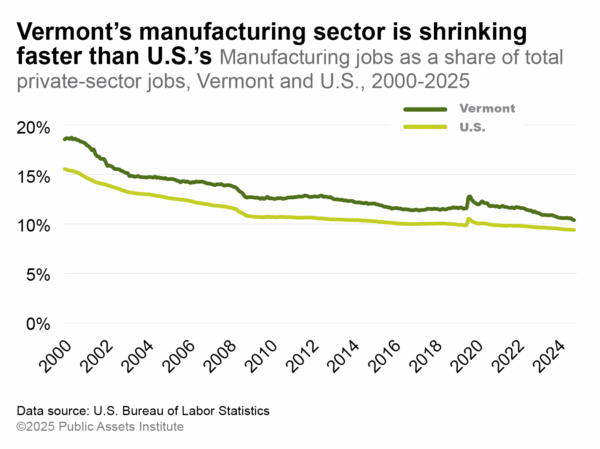

Manufacturing jobs have been declining for decades—and that decline has been bigger in Vermont than the nation overall.

In the last 25 years Vermont has lost nearly 20,000 manufacturing jobs, and manufacturing’s share of private-sector jobs has declined by nearly half. In July 2000, Vermont had 46,200 jobs in manufacturing—more than 18 percent of the state’s private-sector jobs. Last month the state’s 26,900 manufacturing positions accounted for just over 10 percent of jobs offered by private employers. Over the same period, the share of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. as a whole declined less sharply, from 15 percent to just over 9 percent.

Although manufacturing jobs generally offer higher pay, the wages for these positions in Vermont have not increased as quickly as the average wage for all private-sector jobs over the same quarter-century. In fact, manufacturing wages in Vermont have not kept pace with inflation, unlike manufacturing wages nationally, which have seen real growth over time.

Most Vermont workers’ pay has not kept pace with the growth of their output. From 2000 to 2024, productivity—total income generated in the economy per average hour of work—grew 47 percent in Vermont. But compensation—measured by the median hourly wage and benefits for production and nonsupervisory workers—rose by just 34 percent.

Most Vermont counties saw an increase in jobs between 2023 and 2024, according to new data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. But several were still struggling to make up the losses they suffered during the Covid pandemic. Ten of Vermont’s 14 counties added jobs last year; eight still had fewer jobs than in 2019. Rutland faced the largest gap. Even after adding 172 jobs in 2024, it had nearly 1,500 fewer jobs than before Covid. Windham County added the most jobs last year (703), followed by Washington County (484), and Caledonia County (142) was fourth after Rutland.

If and when the governor and Legislature agree on something they call “transformational educational reform,” it’s unlikely to be what most people expected or wanted. Vermonters won’t see the property tax relief they were hoping for because changes to the funding system will be a few years off. Instead, the first signs of reform will be reorganization of their school districts, which they didn’t ask for. On top of that, democratic decision-making on school budgets will be a thing of the past.

Vermonters may be feeling the effects of a tightening job market. Job openings in the state have fallen to their lowest level since November 2020, dropping by 4,000 positions between February and March. These openings include both full-time and part-time jobs for which employers are actively recruiting. Some of the decrease is due to employers filling positions, and some is likely due to postings getting pulled down. Meanwhile, the number of unemployed Vermonters increased over the same period, leaving fewer job openings per unemployed person. The last time Vermont had such a low number of openings per person seeking work was March 2021.

The two most pressing problems in public education are the unfairness in who pays school taxes and the cost drivers out of schools’ control. Current proposals in Montpelier won’t solve either of these problems. We can provide immediate tax relief to thousands of Vermonters by updating income sensitivity and ultimately moving to income-based taxes. And we can address the cost drivers without slashing school budgets, forcing consolidation, or taking away Vermonters’ say in their schools.

Vermont produced $45.7 billion in goods and services last year. That was a 2.3 percent increase in the state’s gross domestic product, after adjusting for inflation. The increase was better than the previous year, but the smallest increase among the New England states.

Meanwhile, Vermont total personal income reached $45.5 billion in 2024. That represented a 4.9 percent increase from 2023, but the smallest increase in the New England states and smaller than the country as a whole.

Now that the House has passed an education reform plan, it will be easy to get bogged down in the minutiae that differentiate it from Gov. Phil Scott’s “Education Transformation Proposal.” But before Vermonters get lost in the weeds debating these proposals, they might want to ask themselves if they support the radical change that both plans represent:

-Are they ready to abandon the idea that taxation for public education should be based on residents’ ability to pay and that a person’s income is the fairest measure of that ability?

-Are they ready to take control of education spending away from local voters and cede it to the Agency of Education?

Homestead exemptions perpetuate unfairness – testimony by Steph Yu:

Since the 1970s, the state has been moving towards basing school taxes on income because the value of your primary residence is not a good measure of your ability to pay. For low- and middle-income Vermonters with mortgages, the value of the primary home overstates their ability to pay because their home equity is less than the home value. And many taxpayers have other debt so may even have a negative net worth. And at the high end, the primary residence is a small share of their wealth and understates their ability to pay. Any homestead exemption structure perpetuates the regressivity of the current system—meaning that higher-income taxpayers pay a smaller share of their income in school taxes than middle-income Vermonters.

The news this Women’s History Month is that women and men share an equal presence in the Vermont workforce. But the workforce is highly segregated by sex. Both men and women work in occupations where one sex accounts for at least two-thirds of the workers.

Many of the state’s social services, such as education and healthcare, rely on women’s labor. Women fill roughly three-quarters of Vermont’s more than 28,000 jobs in educational instruction, including tutors, librarians, teaching assistants, and teachers at all education levels. They represent a similar share of jobs in healthcare, office and administration, and social services occupations, including counseling, social work, and therapy.

Good Public Schools & Fair Taxes – testimony by Steph Yu:

The most pressing problem with education funding isn’t how much we spend.

The two biggest problems we face in education funding are unfairness in who pays school taxes and cost drivers out of districts’ control like teacher healthcare and inflation.

There are two ways in which how we pay for education taxes are unfair now:

1. The richest Vermonters pay a smaller share of their income in school taxes than low and middle-income Vermonters;

2. Income sensitivity has gotten out of whack for many low and moderate-income Vermonters, leaving them facing tax cliffs that can double their bills from one year to the next. This is because the thresholds determining income sensitivity have not been updated in decades.

Teacher health insurance, inflation, and rising demand for special education services and mental healthcare for kids are biggest cost drivers in school budgets and are outside of school districts’ control.

These aren’t school funding problems; they’re societal issues.