It’s time to raise Vermont’s minimum wage

The purpose of the minimum wage is to provide a floor for most workers’ hourly pay. Policymakers already agree that Vermont should continue to set a minimum. The question is whether now is the time to raise it. An assessment of economic indicators shows that low-wage workers, especially those making minimum wage, have lost ground compared with higher-wage workers and compared to the cost of living.

To make life affordable for all workers, Vermont should raise the minimum wage now.

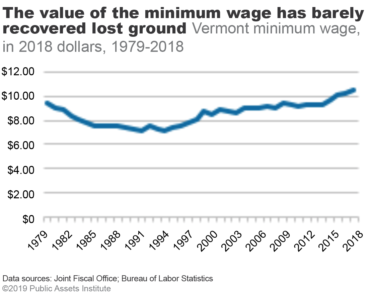

Vermont’s minimum wage is currently $10.78 and is indexed to grow with inflation each year. That indexing began in 2007, although legislated increases from 2014 to 2018 outpaced that rate before returning to it. Even with those adjustments, however, the minimum wage has barely recovered the ground it lost since 1979—it caught back up, adjusted for inflation, only in 2015. Meanwhile, the costs of essentials such as housing, child care, and college have grown much more quickly than pay. That means that workers making minimum wage are worse off than they used to be, and more and more families are struggling to make ends meet. The indicators below point to the need for an increase.

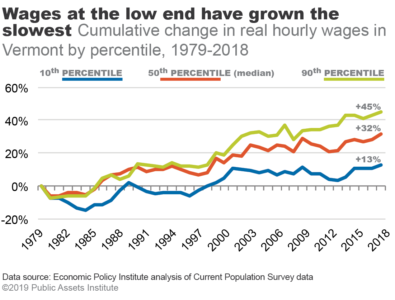

1. Increases have lagged for low-wage workers.

Since 1979 real 1 annual wages for workers at the low end of the scale have barely budged. They linger just 13 percent—or $2,500—above where they were 40 years ago. Meanwhile, the highest-wage earners saw an increase of more than $26,000 in annual wages over the same period, although that growth has slowed in the last decade as well.

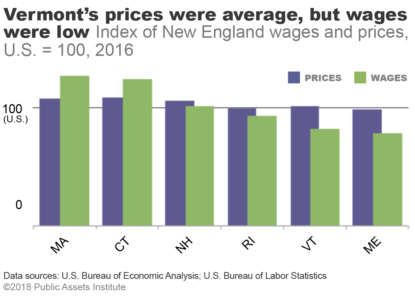

2. Subpar pay, not high prices, set Vermont apart.

More than costs or prices, low and stagnant wages are the reason Vermonters cannot make ends meet. Compared with the U.S. as a whole, Vermont’s prices are average. But wages are low—almost 20 percent below the national average. Vermont also has the second-lowest wages among the New England states.

3. The minimum wage has finally surpassed its 1979 level, while costs for families have soared.

Until 2015 the real minimum wage was lower than it was 40 years earlier. But while it reached its 1979 level that year, adjusted for inflation, the costs of major expenses for families have soared.

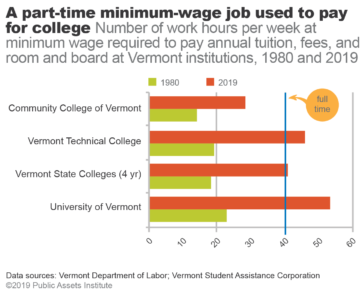

College. In 1980 a person working part time for minimum wage could afford community college; a half-time job could pay for an education at any state school. By 2019 that same individual would have to work twice as many hours to pay for community college. The cost of attending the University of Vermont grew eightfold from 1980 to 2019—much faster than inflation and more than twice as fast as the minimum wage. Over that period the wage increased from $3.10 per hour in 1980 to $10.78 in 2019.

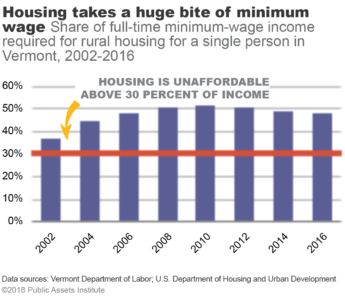

Housing. The minimum wage has not kept up with the cost of housing. In 2017, nearly two-thirds of Vermont households with incomes under $50,000 paid more than 30 percent of their earnings toward housing—the definition of unaffordability. Growth in rental costs and stagnant wages are both to blame for this situation. In 2002, even in less expensive areas of Vermont, a full-time worker making minimum wage would have spent 37 percent of income on housing. By 2016, housing would consume nearly half a minimum-wage income.

Correction: Chart 1 labeling error corrected on 5/21/19.

This issue brief was funded in part by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We thank them for their support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the Public Assets Institute and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation.

- adjusted for inflation[↩]