Vermont response to federal actions:

What is already happening and what else is needed?

See more

See more

In 1997 the Vermont Supreme Court declared the state’s education financing system unconstitutional and required that the Legislature devise a system that provides substantially equal access to public education resources for all of the state’s children, regardless of the wealth of the community they live in. That is what Act 60 accomplished. Before Act 60, property-wealthy communities could raise lots of money for their schools with low tax rates, while property-poor communities had high rates and still were not able to raise much.

Now school tax rates in each town are determined by the amount of money the voters choose to spend per student. The more a school district spends per pupil, the higher the district’s tax rate. Because local decisions vary, school tax rates vary from town to town. Districts with the same per-pupil spending have the same tax rates. About two-thirds of Vermont homeowners pay school taxes based on income

Vermont residents have two options for calculating the school taxes on their primary residence and up to two acres of land. The tax can be based on property value or household income. About two-thirds of Vermont homeowners pay school taxes based on income.

All non-residential property—commercial property, undeveloped land, and second homes—is taxed at a single statewide rate set by the Legislature each year. The non-residential rate does not vary from town to town with per-pupil spending.

The tax system is fair because similarly situated taxpayers are treated the same and education resources are shared by all students.

It favors high-income Vermonters. While the system ensures that most homeowners are taxed based on their ability to pay, a third still pay based on property value. Many high-income taxpayers get a better deal than other Vermonters.

It’s confusing. Because towns and the state assess property values differently, the state-assessed tax rate can be different from the rate the town charges property owners. This disconnect leaves voters frustrated and uncertain as to what is driving the changes in their school property taxes.

The way to fix these problems is to eliminate the school property tax on primary residences and move the remaining third of homeowners to the income-based system.

• All Vermonters’ house sites (primary residence plus adjacent 2 acres) would be exempt from school property taxes.

• All other property would be taxed at the uniform nonresidential rate.

• All residents would pay school taxes based on their adjusted gross income.

• Individual town rates still would be determined by per-pupil spending in that town.

• Renters would pay the town income rate but get a credit for their share of the landlord’s school taxes.

It makes the school tax system less regressive.

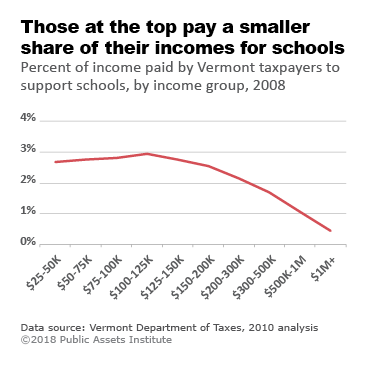

Even with income sensitivity and other features of Act 68—an amended version of Act 60, passed in 2003—low- and middle-income Vermonters are paying more as a percentage of their income than those at the top. This is the definition of a regressive tax. Educating children is one of the state’s most important obligations, and Vermonters should contribute to the support of public education according to their ability to pay. This plan requires all Vermonters, including high-income taxpayers, to pay their fair share.

It’s based on each taxpayer’s ability to pay, and income is the best measure of that ability.

It goes from two systems—one for high-income people and one for low- and middle-income people—to one system for everyone.

Most homeowners with household incomes under $90,000 pay based on income now, and most above $90,000 pay based on property value. But there are also many taxpayers who pay some of each because of where their incomes and property values fall. This plan would be more transparent to voters and would eliminate the unnecessary, confusing, and unfair property tax on primary residences.

It makes the tax consequences of a school budget vote much easier to understand.

Under the current dual systems, taxpayers need a lot of information to estimate their school taxes. This plan would:

• eliminate the Common Level of Appraisal adjustment for residential school taxes

• eliminate the need for income adjustment to property taxes

• eliminate paying both property and income taxes on house sites

• eliminate the need to set two yields (property and income) for primary residences and two rates for each town (property and income)

Under an income-based system, taxpayers would need only two numbers to understand the tax consequences of their school budget vote: their income and the town tax rate.

Aren’t income taxes more volatile than property taxes?

No. The total revenue from property taxes looks more stable because each year the state changes the property tax rates to ensure the necessary revenue is raised, which does not happen with the income tax rates. In fact, over the last 20 years total income in the state has been steadier than the Education Grand List, the total taxable property value for school taxes.

And from the individual taxpayer’s perspective, if your income goes down, you want your school tax bill to go down. Property taxes do not change when a taxpayer’s income changes.