Public investments move the state forward

As legislative leaders prepare to tackle pressing issues confronting Vermont, the Scott administration has signaled that they shouldn’t be looking to state government for any more help. If the Legislature wants to combat climate change, expand the availability of high-quality child care, or extend paid family and medical leave benefits, any new investments will have to come from existing programs because state government is doing all it can do.

At least that seems to be the clear implication of the letter sent early last month to House Speaker Mitzi Johnson and Senate President Pro Tem Tim Ashe:

“It is our view that if the percent of a household’s income captured by government is increasing, government is having a regressive economic impact on households,” Administration Secretary Susanne Young wrote, as part of a document about projected education tax rates for the coming year.

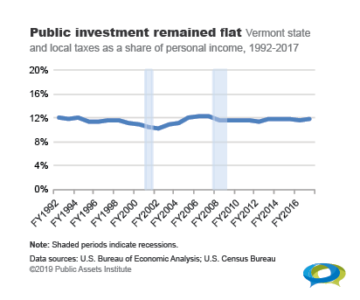

State of Working Vermont 2019, which we released just before Christmas, includes this chart showing that state and local taxes collected in Vermont, as a percentage of Vermonters’ total personal income, remained flat for 25 years.  (We included state and local taxes because money for schools was raised primary through local taxes until 1997. Now education funding is generated by state taxes.)

(We included state and local taxes because money for schools was raised primary through local taxes until 1997. Now education funding is generated by state taxes.)

In fiscal 2017—the latest year data are available and the year Governor Scott took office—state and local taxes were 11.8 percent of Vermonters’ total personal income. In fiscal 1992, taxes were 12 percent of personal income, and they averaged 11.6 percent over the entire period.

According to the Scott Doctrine, however much money Vermont’s tax system was generating when he took office—as a share of income—is all that Vermonters can afford. And he’s saying despite the changes we’ve seen in the last generation—the rise in health care costs and fuel prices, the opioid epidemic, the need for high-quality child care, climate change, security threats, the explosion in telecommunications—that the level of Vermont public resources available in 1992 is adequate for the world we live in today.

The Scott Doctrine is based on the governor’s belief that public investments make Vermont unaffordable.

“One of the key performance indicators we use to measure how effectively state government is helping to make Vermont more affordable for families is the percent of household income (HHI) spent on state taxes—and fees,” Secretary Young said in her letter.

But for Vermonters struggling with affordability, it’s low wages that are at the root of the problem. State of Working Vermont 2019 shows that prices, as calculated by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), were only slightly higher—2.5 percent—in Vermont than the national average. Vermont’s average wage, meanwhile, was 18 percent lower than the U.S average wage.

Vermont’s fiscal policies—decisions about how much to raise and invest—should be based on continuing and up-to-date assessments of what it will take for Vermont to meet today’s challenges—not the ones the state faced 25 years ago. Planning and investing in the future is the way Vermont moves forward. The Scott Doctrine has the effect of actually holding the state back.

I wonder if this administrative push is also behind the State’s apparent threat to let the Brattleboro Retreat fold, throwing mental health services into a state of chaos(see https://www.vpr.org/post/scott-administration-says-brattleboro-retreat-slated-possible-closure)? If you juxtapose this data on overall tax rates with data on the tax rate for the upper income earners, wouldn’t that clearly show that SOME people’s contribution has dropped while the rest of us pick up the burden? Your mission, should you choose to accept it: get both factors on one chart.