NEW REPORT:

Migration: Millennials and the wealthy moved in. Most Vermonters stay put

Read the report

Read the report

Vermont made headlines last week when the U.S. Census released its latest statistics for 2016: We were the only state to show an increase in the poverty rate. That may have been an artifact of the Census survey sample. The poverty rate showed an unusual drop in 2015, and 2016 looks more like a return to normal than a real increase.

The Census released another poverty report week week that didn’t get as much attention. The Supplemental Poverty Measure report tells a different story and the data contain more encouraging news: public services and assistance do lift people out of poverty.

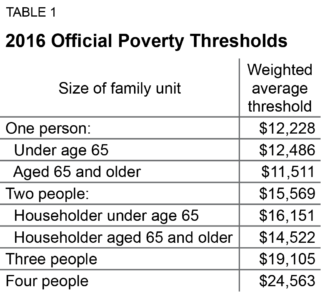

The official poverty measure is widely seen as outdated because it doesn’t take into account the anti-poverty programs and policies adopted in the last 50 years. Created in the late 1960s, the official measure of need was calculated as three times the cost of a minimum food diet for families of varying sizes. The family’s pre-tax cash income determined whether it was above or below this calculated “poverty threshold.” (See Table 1.)

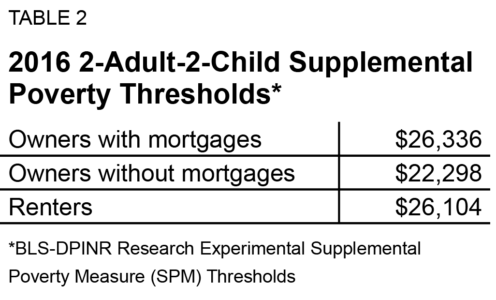

The Supplemental Poverty Measure recognizes that tax credits and other benefits are available to low-income families to help them meet their basic needs. So non-cash benefits are counted along with cash income—minus taxes and certain work expenses—to determine a family’s resources. On the cost side, the Supplemental Poverty Measure uses a more realistic estimate of basic needs like food, shelter, clothing and utilities. The Supplemental Poverty thresholds are somewhat higher, but the poverty measure takes into account additional resources.

For state level data, the Census uses three-year averages to calculate Supplement Poverty Measures. Vermont’s Supplement Poverty Measure for 2014-2016 was 8.6 percent, according to new data released this week. The state’s “official” poverty rate for the same period was 9.9 percent.

Because the Supplemental Poverty Measure takes into account things like food stamps (known as 3SquaresVT in Vermont), the Earned Income Tax Credit, and other forms of public assistance, it’s possible to calculate the effects of these efforts. A 2015 analysis by The Center on Budget Policies and Priorities in Washington, D.C. concluded that an average of 96,000 more Vermonters would have been below the Supplement Poverty Threshold if they had not received government assistance. 1 According to the CBPP report, Vermont’s Supplemental Poverty Measure was 8.2 percent for the period analyzed—instead of the 23.7 percent rate it would have been without public policies and programs to help low-income families.

Because the Supplemental Poverty Measure takes into account things like food stamps (known as 3SquaresVT in Vermont), the Earned Income Tax Credit, and other forms of public assistance, it’s possible to calculate the effects of these efforts. A 2015 analysis by The Center on Budget Policies and Priorities in Washington, D.C. concluded that an average of 96,000 more Vermonters would have been below the Supplement Poverty Threshold if they had not received government assistance. 1 According to the CBPP report, Vermont’s Supplemental Poverty Measure was 8.2 percent for the period analyzed—instead of the 23.7 percent rate it would have been without public policies and programs to help low-income families.

Vermont has to do more to increase wages so that full-time work pays enough to support a family. But it also has an obligation to maintain support for services that do lift Vermonters out of poverty.

Comment Policy

We welcome and publish non-partisan contributions from all points of view provided they are of a reasonable length, pertain to the issues of Public Assets Institute, and abide by the common rules of online etiquette (i.e., avoid inappropriate language and “SCREAMING” (writing in all caps), and demonstrate respect for others).